寒假入门一下 Python,主要关注语法特性。中英文可能混杂,塑料英语见谅。

加入了部分 CS50 的内容。

原版英文笔记见 https://cs50.harvard.edu/python/2022/notes/。

Lecture 0-5: Intro

注意 Python 和 C/C++ 的简要区别:

- 函数体可被传参,可返回 multiple values(实质是 tuple 的封包/解包)。元组的不可变是指元组所指向的内存中的内容不可变。

- 完全不同的变量作用域/可覆盖机理,依照解释器调用顺序而非编辑器顺序。

- Python 中只有模块(module),类(class)以及函数(def、lambda)才会引入新的作用域,其它的代码块(如 if/elif/else/、try/except、for/while等)是不会引入新的作用域的,也就是说这些语句内定义的变量,外部也可以访问。

- 注意:内部作用域想修改外部作用域的变量时,需使用 global 和 nonlocal 关键字。如果不使用 global,则这个变量只读。

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8num = 1

def fun1():

global num # 需要使用 global 关键字声明

print(num)

num = 123

print(num)

fun1()

print(num) - 多变量赋值,见后文 Unpacking 部分。

- 使用 for … in … 循环。更确切地说,习惯使用

in关键字,以处理复杂类型的成员:We use1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9people = {

"Carter": "+1-617-495-1000",

"David": "+1-949-468-2750"

}

name = "David"

if name in people:

number = people[name]

print(f"Number: {number}")if name in people:to search the keys of our dictionary for aname. If the key exists, then we can get the value with the bracket notation,people[name].

Sequences

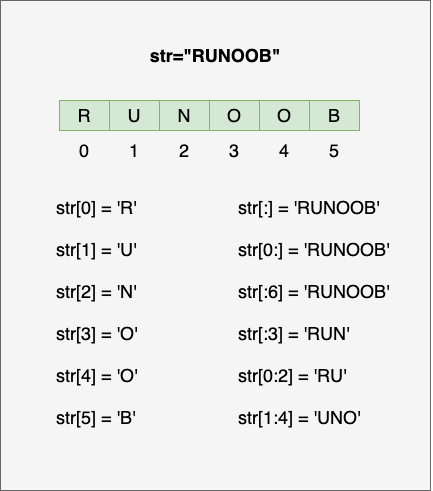

- 对于 str,可以进行

if "You" in "DoYou Can":。 - f 字符串

print(f"Hello, {name}")。详细用法现查。

1 | >>> x = 1 |

- 字符串的运算符。

[::]Slice:

- 第三个参数可接收步长,常见用法是正数或

[::-1]。

Features

- Perhaps useful:

random.choice([list]) random.shufffle([]),str.upper().lower().title()。 - sorted(),用法见后文。

sys.argv (-> list)读取 command line 的内容。assert断言来终止程序。- try … except … else … finally

- 可以 except 一个元组,内含多个异常。

- A simple sample of

requests:

1 | import requests |

- Keyword

match:

1 | match name: |

- pytest 及其文件组织方式

1 | | hello.py |

whereas `test_hello.py` will be treated the same level as `hello.py`, i.e., you can `import hello` in `test_hello.py`.

run `pytest test`.

- We can use the

withkeyword, which will close the file for us after we’re finished:

1 | with open("phonebook.csv", "a") as file: |

Lecture 6,7 are skipped.

Lecture 8: OOP

- 注意 str 和 keys:dict 的引号冲突。

- The order of the keys is typically remembered.

student = Student()is creating an object/instance of that class.- You can consider

nameas an attibute whilestudent.nameis accessing an instance variable. - 类的 attributes 不必事先声明。

- keyword

raise,制造异常配合 try…except。 - What is attibute?类的属性

An attribute is anything that comes after a dot.

A property is always a function in python. __init__, __str__@property实现对成员赋值的加工处理

重要 如果设置了 ‘getter func’@property \n def house(self), and after that, ‘setter func’@house.setter \n def house(self, house),那么当操作object.house时上述函数会被自动调用。似乎拥有先后次序。它们均可以被__init__调用,尽管似乎位置顺序相反。

然而,这样做会引起 func house 和 instance var house 的冲突。conventional solution 如下:

1 | class Student: |

So now technically we have

- instance var

_house; - property(an attribute)

house.

注意!object._house是 accessible 的。Python 没有 public/private/protected 关键字来限制访问。

property 的访问形式与 instant var 相同,e.g.student.house = "Ravenclaw"作为其语法糖。

- 留意函数 str.strip(), list.append(), type()。

@classmethod使得其不依赖类的实体而被调用。- Class variable exists only once:

1 | class Hat: |

因此,借助此修饰可以将读取并创建实例的工作整合进 class 里。

1 | class Student: |

注意:technically 这里的 cls() 当然可以使用 Student() 来替代。推测可能是出于后续继承等的原因。在这个程序段中,此处的 cls 总是当前类。

Inheritance

Inheritance: Design your classes in a hierarchical(分层) fashion. 避免 duplication。

1 | class Wizard: |

多继承暂时 skipped。

重载运算符

Python 支持重载运算符,需查询相应符号对应的保留函数名。

1 | class Vault: |

这里的左右类型不必相同。

Lecture 9: Et Cetera

set

-

In math, a set would be considered a set of numbers without any duplicates.

-

In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15students = [

{"name": "Hermione", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Harry", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Ron", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Draco", "house": "Slytherin"},

{"name": "Padma", "house": "Ravenclaw"},

]

houses = []

for student in students:

if student["house"] not in houses:

houses.append(student["house"])

for house in sorted(houses):

print(house)Notice how we have a list of dictionaries, each being a student. An empty list called

housesis created. We iterate through eachstudentinstudents. If a student’shouseis not inhouses, we append to our list ofhouses. -

It turns out we can use the built-in

setfeatures to eliminate duplicates. -

In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14students = [

{"name": "Hermione", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Harry", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Ron", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Draco", "house": "Slytherin"},

{"name": "Padma", "house": "Ravenclaw"},

]

houses = set()

for student in students:

houses.add(student["house"])

for house in sorted(houses):

print(house)Notice how no checking needs to be included to ensure there are no duplicates. The

setobject takes care of this for us automatically.

Global Variables

-

In other programming languages, there is the notion of global variables that are accessible to any function.

-

Python 建议使用 OOP,尽量规避全局变量的使用。

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25class Account:

def __init__(self):

self._balance = 0

def balance(self):

return self._balance

def deposit(self, n):

self._balance += n

def withdraw(self, n):

self._balance -= n

def main():

account = Account()

print("Balance:", account.balance)

account.deposit(100)

account.withdraw(50)

print("Balance:", account.balance)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Notice how we use

account = Account()to create an account. Classes allow us to solve this issue of needing a global variable more cleanly because these instance variables are accessible to all the methods of this class utilizingself.

Constants

-

Constants are typically denoted by capital variable names and are placed at the top of our code. Though this looks like a constant, in reality, Python actually has no mechanism to prevent us from changing that value within our code! Instead, you’re on the honor system: if a variable name is written in all caps, just don’t change it!

-

One can create a class “constant”:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10class Cat:

MEOWS = 3

def meow(self):

for _ in range(Cat.MEOWS):

print("meow")

cat = Cat()

cat.meow()Because

MEOWSis defined outside of any particular class method, all of them have access to that value viaCat.MEOWS.

Type Hints

-

Python does require the explicit declaration of types. 然而,Python 是强类型语言,几乎不容忍隐式的类型转换。引入 type hint 以便于在正式运行前进行从头到尾推导的类型检查。

-

A type hint can be added to give Python a hint of what type of variable or function should expect. In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8def meow(n: int) -> None:

for _ in range(n):

print("meow")

number: int = int(input("Number: "))

meows: str = meow(number)

print(meows)

Docstrings

-

You can use docstrings to standardize how you document the features of a function. In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16def meow(n):

"""

Meow n times.

:param n: Number of times to meow

:type n: int

:raise TypeError: If n is not an int

:return: A string of n meows, one per line

:rtype: str

"""

return "meow\n" * n

number = int(input("Number: "))

meows = meow(number)

print(meows, end="") -

Established tools, such as Sphinx, can be used to parse docstrings and automatically create documentation for us in the form of web pages and PDF files such that you can publish and share with others.

-

You can learn more in Python’s documentation of docstrings.

argparse

- You can learn more in Python’s documentation of

argparse.

Unpacking

-

一个序列 seq 在去赋值和传参时会被自动解包。赋值举例:

1

2first, _ = input("What's your name? ").split(" ")

print(f"hello, {first}")‘=’ 左右变量的个数必须相同。注意,这里等号的左侧事实上也是一个被解包的序列,其类型可以被指定但没有必要。比如,下面的写法是可被接受的:

[s, _] = "Your name".split() -

A

*unpacks the sequence of a list(seq) and passes in each of its individual elements to a function:1

2

3

4

5

6

7def total(galleons, sickles, knuts):

return (galleons * 17 + sickles) * 29 + knuts

coins = [100, 50, 25]

print(total(*coins), "Knuts")被解包后的序列本身没有类型、不能做左右值,不能在程序中独立存在。用于传参时,等价于传入恰好数量的 arguments。

-

解包 dict 时,会把 key 的内容去引号解析为 parameters, 相当于指定参数名地传参。理所当然地,dict 内部的顺序对结果没有影响。

1

2

3

4

5

6

7def total(galleons, sickles, knuts):

return (galleons * 17 + sickles) * 29 + knuts

coins = {"galleons": 100, "sickles": 50, "knuts": 25}

print(total(**coins), "Knuts")

args and kwargs

-

Recall the prototype for the

printfunction:1

print(*objects, sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False)

-

We can tell our function to expect a presently unknown number positional arguments. We can also tell it to expect a presently unknown number of keyword arguments. In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9def f(*args, **kwargs):

print("Positional:", args)

print("Named:", kwargs)

>>> f(100, 50, 25)

Positional: (100, 50, 30)

Named: {}

f(120,4, name='C', tin='UNI')

Positional: (120, 4)

Named: {'name': 'C', 'tin': 'UNI'} -

argsare positional arguments, such as those we provide to print likeprint("Hello", "World"). 类型为 tuple. 接收未指定名称的参数。 -

kwargsare named arguments, or “keyword arguments”, such as those we provide to print likeprint(end=""). 类型为 dict. -

可以使用

kwargs接收所有被指定 parameter 名的参数,也可以在函数定义处指明你关心的特定名称的参数。 -

In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13def main():

yell("This", "is", "CS50")

def yell(*words):

uppercased = []

for word in words:

uppercased.append(word.upper())

print(*uppercased)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Notice how

*wordsallows for many arguments to be taken by the function.

map

-

Hints of functional programming: where functions have side effects without a return value.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10def main():

yell("This is CS50")

def yell(word):

print(word.upper())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Notice how the

yellfunction is simply yelled. -

map(func, iterable) 将 iterable 的每一项用 func 作用后,返回这个整体。

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11def main():

yell("This", "is", "CS50")

def yell(*words):

uppercased = map(str.upper, words)

print(*uppercased)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

List Comprehensions

-

List comprehensions allow you to create a list on the fly in one elegant one-liner.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13students = [

{"name": "Hermione", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Harry", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Ron", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Draco", "house": "Slytherin"},

]

gryffindors = [

student["name"] for student in students if student["house"] == "Gryffindor"

]

for gryffindor in sorted(gryffindors):

print(gryffindor)

Dictionary Comprehensions

-

Notice how the dictionary will be constructed with key-value pairs.

1

2

3

4

5students = ["Hermione", "Harry", "Ron"]

gryffindors = {student: "Gryffindor" for student in students}

print(gryffindors)

filter

-

filter(function, iterable) 将 iterable 的每一项判断 func 作用后是否为真,返回结果为真的相应值的整体。

-

filtercan also use lambda functions as follows:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12students = [

{"name": "Hermione", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Harry", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Ron", "house": "Gryffindor"},

{"name": "Draco", "house": "Slytherin"},

]

gryffindors = filter(lambda s: s["house"] == "Gryffindor", students)

for gryffindor in sorted(gryffindors, key=lambda s: s["name"]):

print(gryffindor["name"])

enumerate

-

We may wish to provide some ranking of each student. In the text editor window, code as follows:

1

2

3

4students = ["Hermione", "Harry", "Ron"]

for i in range(len(students)):

print(i + 1, students[i])Notice how each student is enumerated when running this code.

-

Utilizing enumeration, we can do the same:

1

2

3

4students = ["Hermione", "Harry", "Ron"]

for i, student in enumerate(students):

print(i + 1, student)Notice how enumerate presents the index and the value of each

student. -

You can learn more in Python’s documentation of

enumerate.

Generators and Iterators

-

当需要生成一个 iterable 并对其每一项操作时,在生成函数中使用 yield 使得 iterable 每生成一项便传入相应操作中处理。一次操作完成后,生成器再生成第二项传入,以此类推,以避免 iterable 的体积过大。

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14def main():

n = int(input("What's n? "))

for s in sheep(n):

print(s)

def sheep(n):

for i in range(n):

yield "🐑" * i

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()Notice how

yieldprovides only one value at a time while theforloop keeps working.